PRSA is offering the following resources during Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Month.

The latest in PRSA’s “Diverse Dialogues” series explored how communicators and PR educators should proceed in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic decision on June 29 that effectively ended race-conscious admission programs at colleges and universities across the country.

Cayce Myers, Ph.D., APR, professor and director of graduate studies at the Virginia Tech School of Communication, moderated the session on Sept. 13 titled “Bridging Equality: Communicating Post-U.S. Supreme Court Decisions.” He began by asking the panelists how they define diversity, equity and inclusion.

At historically Black colleges and universities, diversity introduces students “to broader social and political perspectives, which we believe form the foundation of civil discourse,” said panelist Richelle D. Payne, vice president for strategic communications and marketing at Hampton University, a historically Black institution in Virginia.

“Just 7% of PR communicators are Black, but top talent is Black talent,” Payne said. At her school, “meritocracy and equal access are alive and well.”

Panelist Natalie Tindall, Ph.D., APR, director of the Stan Richards School of Advertising & Public Relations at the University of Texas, said, “Why aren’t there more people of color in public relations? Let’s talk about the pipeline issues that exist and the structures that cause students and people of color to leave the profession.”

A more perfect union?

On July 4, 1776, the 13 colonies declared independence from Great Britain, calling themselves the United States of America. The Revolutionary War, fought by a ragtag American army, would grind on for eight more years before that freedom was truly gained.

The Declaration of Independence says that “all Men are created equal,” but in the view of panelist James C. Burroughs II, a senior vice president and chief equity and inclusion officer at Children’s Minnesota, a pediatric health system, “The reason that we have the necessity for [DEI] programs is this country was founded on the principles of racism.”

In 2023, some businesses are turning away from their DEI efforts “because they are fearful of lawsuits,” of being targeted by people who don’t share their values, Burroughs said. Some companies, he said, are “fearful of doing things that will make this an equitable and just country.”

After the Supreme Court’s ruling on affirmative action in college admissions, “Now it’s a convenient time for companies to say, ‘Well, maybe we’ve done enough,’” Burroughs said. “This country was founded in 1776, but from 1776 until 2020 you had a whole lot of systems that led to the disparity we have.”

At Children’s Minnesota, executive bonuses are tied in part to equity and inclusion, Burroughs said. The company’s executives each have an equity coach. “We hold them accountable,” he said.

In his view, “‘Polarizing’ is sometimes just a buzzword that means, ‘I don’t want to talk about it,’” Burroughs said. “But we need to keep talking about it.”

Consequences of cutting DEI programs

Concerns about equality tend to be cyclical, Tindall said. “We have seen this time and time again, where the issues of diversity, equity and inclusion come to the front burners. And then we oftentimes see those issues move to the backburner, because other things pop up. Now, we’re seeing issues about the global economy and legal challenges shifting the focus away from diversity, equity and inclusion.”

The fear, Tindall said, “is that a lot of companies already made shallow and hollow commitments after George Floyd’s murder in 2020, and now they’re walking back some of those shallow and hollow commitments. They did the equity talk, but not the equity walk.”

One of Payne’s former clients, a financial services firm, needed a DEI-communications program and wound up building a robust communications operation. At the same time, however, the company would send its employees intranet announcements that only involved company personnel at the level of director or above.

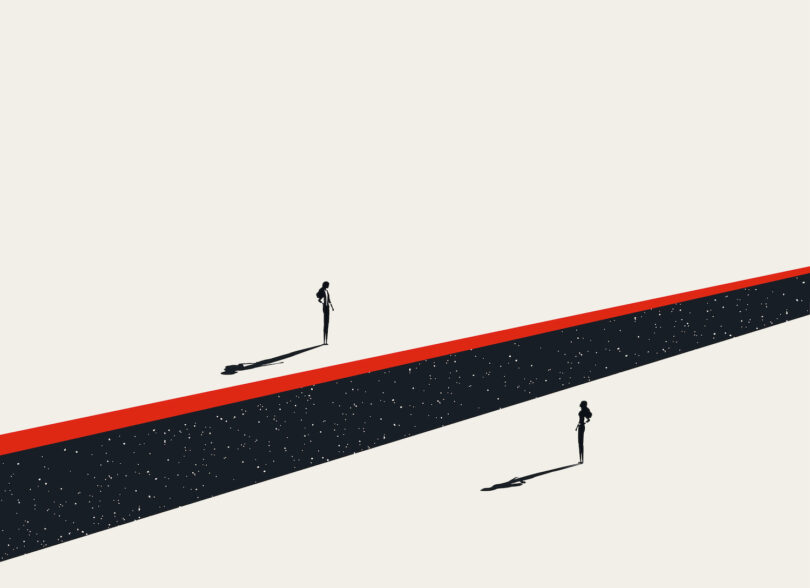

The imagery that regularly appeared on the company’s intranet “was all white men,” Payne said, “because the white men were getting the director-and-above positions. It was very disheartening, very demotivating and very tone-deaf.”

When you think about DEI programs, Payne said, “the messaging and the images and the ideologies are centered on white normativity, the unconscious and invisible ideas and practices that make whiteness appear natural and right. It’s the dominant culture that has the problem.”

In DEI communications, “We have to think about the alignment, the authenticity and the credibility of the speaker, which is the organization,” Tindall said. “Oftentimes, the images that companies use don’t align with what they’re trying to accomplish.”

On Jan. 6, 2021, “when the U.S. Capitol was stormed, I was on a conference call with people and we were talking about purpose in organizations,” Tindall recalled. “If your corporate social speeches say, ‘We don’t believe in this, we think this is abhorrent,’ and yet your lobbying dollars go to the people who supported that activity, you all are not in alignment.”

The larger picture of what communications is supposed to accomplish, Tindall said, is “to effect social change.”

PRSA members can watch a playback of the session here.

[Illustration credit: jozefmicic]