With any communication campaign, “the key is understanding what we’re trying to achieve,” said Rear Adm. Charles Brown, APR+M. “Start with the outcomes in mind” and then “measure whether you’ve achieved them,” said Brown, the Navy’s chief of information.

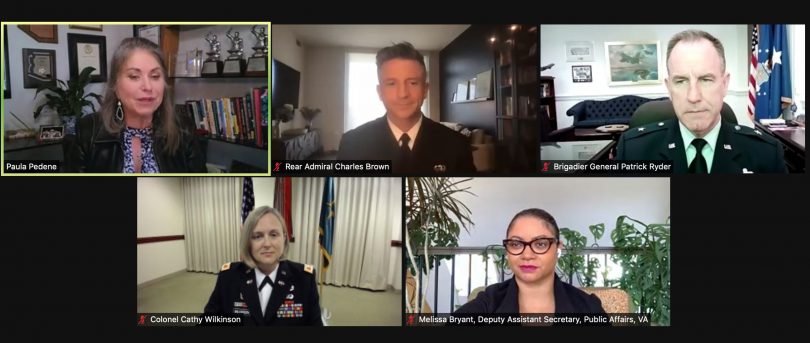

Brown was one of four U.S. Military communicators who were guest panelists for PRSA’s Oct. 14 virtual keynote session, “Navigating Your Communication by Utilizing a Military Mindset,” during ICON 2021.

Ask, “What are the communication objectives?” said Brig. Gen. Patrick S. Ryder, director of public affairs in the Office of the Secretary of the Air Force. Ryder is responsible for communications to build public understanding and support for the Air Force and the newly formed Space Force. Among the questions he must answer: “What is Space Force and why do we need one? What are the threats in space and what do they mean to our national security?”

Col. Cathy Wilkinson, U.S. Army media relations director at the Pentagon, emphasized the continuing importance of the human factor in communication during the digital age. “Relationships matter,” she said. “Pick up the phone and call someone. Don’t rely on emails, don’t rely on chat. Meet people in person.” Remember that “words and tone matter.”

Choosing the right tone comes from knowing your audience, said Melissa Bryant, deputy assistant secretary of the Office of Public Affairs for the Veterans Administration. The agency has different audiences — veterans, the press and the public at large. To communicate messages that help veterans in crisis, Bryant goes beyond traditional PR vehicles such as press releases and works with TV and film producers. “We need to go where the audience is,” she said.

Filtering information and communicating during a crisis

Moderator Paula Pedene, APR, Fellow PRSA and a U.S. Navy veteran, asked panelists about best practices for “filtering information through the fog of war.”

When initial reports arrive during a crisis, “The first and most important thing is to have a healthy skepticism” and not inadvertently echo erroneous information to a broader audience, Brown said. “You have to wait and let things develop in order to get an accurate picture of what happened.”

To that end, communicators need to “filter out what’s important and what’s not” and to anticipate what’s coming by maintaining a “high level of situational awareness” that helps exploit opportunities and mitigate risk, Ryder said. Such advice also applies to how PR professionals advise senior leaders and respond to misinformation and disinformation spread on social media and elsewhere.

To avoid being swayed by the media and the court of public opinion, scan the horizon, “see outside of the dominant groupthink” and ask, “Is this an actual problem that we need to address?” Bryant said. To make that determination, “be open to listening to different voices,” Brown said.

Communicators need to understand “what’s important to respond to, so you don’t give it legs and make it an issue where it’s not,” said Wilkinson. The military grapples with the problem of imposters on social media — accounts masquerading as members of the armed services. As Russian “troll farms” spread malicious falsehoods on the internet, many people still “don’t know how to verify information,” she said. Wilkinson recommends literacy training for media and social media.

“We’re in an era where we’re obligated to be more aggressive in calling out misinformation and disinformation,” Brown said. “We can’t assume that bad information will go away.”

Veterans are in a “target-rich environment” for bots and foreign actors that spread misinformation for political gain, Bryant said. To fight these falsehoods, she recommended partnering with veterans-service organizations that share a “sense of duty and patriotism and service to our nation.”

An audience member asked about the value of earning an Accreditation in Public Relations (APR). PRSA offers the APR+M, a joint effort among the Universal Accreditation Board and the Department of Defense to help improve the military public affairs practice and establish a standard of knowledge that is transferable to civilian work.

From an Air Force public affairs standpoint, “We do value accreditation and any kind of professional development that’s going to enhance your skills and make you a better practitioner,” Ryder said. “It is not mandatory within the military, but we certainly encourage our teammates” to earn their APR when possible.

For the Navy, Accreditations are “considered in promotions as part of your professional expertise,” added Brown. “It’s something that can be seen as a differentiator, particularly within government service,” Bryant said. In the Army, Wilkinson said, an APR “shows that someone has gone above and beyond.”