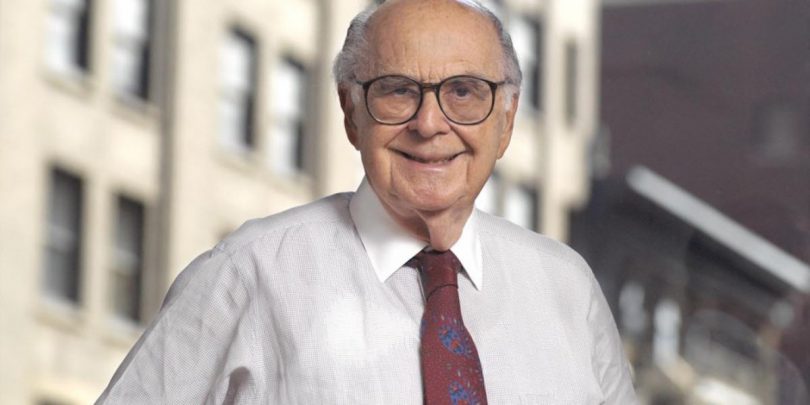

Harold Burson, APR, Fellow PRSA, the distinguished founder of one of the world’s largest PR agencies, died on Friday in Memphis, Tenn. He was 98.

Burson, once described by PRWeek as “the century’s most influential PR figure,” was a PRSA member for more than 70 years, joining in November 1949. He started Burson-Marsteller in 1953 with Bill Marsteller. Under their leadership, the agency became a global powerhouse with 2,500 employees in 50 offices.

In 1979, Burson sold the firm to ad agency Young & Rubicam. He stepped down as his company’s CEO in 1988, though he remained active in agency business and served as a mentor to many communicators and executives. In early 2018, Burson-Marsteller merged with Cohn & Wolfe, creating Burson Cohn & Wolfe.

“Harold was so much more than the heart and soul of Burson-Marsteller, although he surely was that. He stood, for decades, at the top of an entire profession and inspired everyone in our industry — and those we counsel — to want to be like Harold,” Donna Imperato, global CEO of Burson Cohn & Wolfe, said in a statement. “Every one of us who had the opportunity knows what a tremendous privilege it was to have worked with Harold.”

During his distinguished career, he was well known for his candid and wise counsel to leading CEOs. Burson advised Johnson & Johnson during the Tylenol crisis, Union Carbide following the deadly gas leak in India and Coca-Cola during the disastrous New Coke introduction.

In 1980, PRSA honored Burson with the Gold Anvil, the Society’s highest individual award. He was a member of the inaugural class of the College of Fellows in 1989. In a statement, PRSA called Burson “a treasured, generous role model and mentor who helped shape countless generations of students and communications practitioners.”

He was born on Feb. 15, 1921, in Memphis. The son of English immigrants, Burson began working at The Memphis Commercial Appeal, a daily newspaper, when he was 13 years old. He received on-the-spot editing and advice from his editor, which he said was the best training he’s ever had.

After graduating from high school at age 15, Burson went to college at the University of Mississippi and continued as a stringer for the Memphis paper, making 14 cents per column inch. His bylines included a front-page interview with William Faulkner.

Burson enlisted in the Army in 1943 and became part of an engineer combat group in Europe. He and his fellow soldiers helped remove land mines from the beaches at Normandy after the 1944 Allied invasion. In 1945, he was transferred to the news staff of the American Forces Network. Later that year, he reported on the Nuremberg trials. He was the only reporter to obtain an interview during the trial with Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson, the chief American prosecutor.

“If my objective starting out was to have a charmed life, I couldn’t have written the script any better,” he once said.

Burson was married to Bette Foster Burson for nearly 63 years. He is survived by two sons, Scott F. Burson (Wendy Liebow Burson) of Lexington, Mass., and Mark Burson (Ellen Jones Burson) of Westlake Village, Calif., and five grandchildren: Allison Burson, Esther Burson, Wynn F. Burson (Steven Cateron), Holly Burson and Kelly Burson.

“Our family is saddened by the loss of our beloved father. We grieve and mourn his passing. And yet our spirits are lifted by the belief that he is now ‘gathered’ with his loving wife and faithful companion of 63 years — Bette Ann,” the family said in a statement.

Memorial services will be held in New York City and at the University of Mississippi. He will be entombed in the Columbarium at Arlington National Cemetery.

In lieu of flowers, the family asks those wanting to celebrate their father’s life to make a donation to the Harold Burson Legacy Scholarship Fund at the School of Journalism and New Media at the University of Mississippi.

Ed Note: Please share your memories of Harold Burson in the comments section below.

John Elsasser is the publications director at PRSA.

What is remarkable about Harold is that everyone who ever met him, when asked about him, skips all of the resume and awards and legendary leader details, and begins with “He was the nicest man.”

The highest epitaph any of us can aspire to, and in today’s sometimes cut-throat PR industry, that kind of a legacy is hard to maintain decade after decade.

Along with Pat Jackson and Chet Burger and Betsy Ann Plank, the likes of these will not pass our way again.